The future of work is about change.

It’s about how technology and automation are changing the jobs we do and the skills we need. It’s about a globalised workforce, where employees can work from offices, their kitchen table or even another country. It’s about a shift in employee expectations around work-life balance, with individual purpose and group culture becoming ever-more important.

Above all, it’s about how we adapt to the pace of change and deliver the skills we need to keep our businesses, people and economies thriving. Doing so means reimagining how we deliver training and create learning cultures.

Succeeding in the future of work means delivering the future of learning.

Read this guide to understand:

How external factors (e.g. COVID-19) have impacted the skills landscape

How to identify skills gaps in your business

The role learning and development has to play in upskilling the workforce, and also retaining and engaging new and existing talent

How creating a continuous learning culture can boost productivity

Why investing in the development of human skills can help future-proof your organisation in times of change

To understand why the future of learning is the future of work, we need to examine where work sits in our current context.

The shockwaves from the COVID-19 pandemic are still being felt, as organisations get to grips with hybrid working, accelerated digital transformation and the changing needs of employees. Coupled with a gloomy economic outlook and rising inflation, businesses must look for opportunities to thrive amid uncertainty.

Leadership styles and organisational structures have undoubtedly evolved in recent years. The pandemic saw the rise of the empathetic leader – Microsoft CEO Satya Nadella called it “extreme compassion” – who focused on the safety and wellbeing of their employees. This trend is likely to continue, as businesses move away from a 'command-and-control' style of leadership, to more collegiate, inclusive styles.

In an increasingly digitised landscape where many jobs and careers are at risk of automation, our collective challenge is to think harder about what makes us human in an age of AI. How do we complement the technology we have at our disposal? What are the cognitive, social and emotional resources we can nurture to prepare people for the life and work of tomorrow? What are the skills we need?

Before the pandemic, education systems and businesses were struggling to prepare young people with the skills needed to succeed in a drastically altered work landscape. According to the International Labour Organization, 267 million young people were not in employment, education or training in 2020.

Andreas Schleicher of the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) considers the critical skills that will help individuals navigate a new work landscape, and how education, government and society can work together to disrupt the skills systems for a more sustainable future:

Disclaimer: If you are able, we strongly encourage you to watch this video or listen to its audio. Transcripts are generated using speech recognition software that has been checked by human transcribers but may contain errors. Please check the corresponding audio before quoting in print.

Summary keywords: people, learning, labour markets, education, skills, technology, countries, jobs, pandemic, digital, future, longer, scenarios, world, incredibly, systems, work, test, progressing, artificial intelligence

Andreas Schleicher 00:34

Hello and thank you so much for inviting me to your conference on transforming skills and inclusion. These are difficult times even before the pandemic, labour markets were polarising, digitalisation was transforming most of the jobs, inequality kept rising in many countries.

If you think about it, you know, digitalisation has been incredibly democratising. Everybody can collaborate, everybody can contribute. But it's also concentrated power at a rate we've never seen before.

Technology has been incredibly polarising, the smallest slice can be heard everywhere you post something on Twitter, and the world can follow you. But technology has also been incredibly homogenising, squashing individual differences cultural uniqueness.

Technology has been incredibly empowering. The most successful companies these days, you know they have the product before they have the money. They start with a big idea not you know, with a lot of epic industry. But technology has been also incredibly disempowering when we suddenly become the slaves of algorithms that we no longer understand. You think about it, digital platform technology drives the reorganisation of France, we no longer know what's a big and a small company, sometimes very few people can transform the world.

Peer to Peer markets are blurring the distinction between consumers and businesses and even governments are starting to leverage the platform economy. Some people say well, you know automation is taking away jobs. But actually what we see is that digital intensive workplaces are much better at extracting value from the skills of people and converting better skills into better jobs and better lives of people.

And this is not just about technological skills, you can see almost in any skill category, the returns now that our earnings and employment are rising for people in digital intensive industries.

Data from our survey finance skills have also shown you know, where you work in a more digital intensive workplace, you are more likely to learn from your coworkers, you're more likely to learn by doing trying things, finding things out for yourself and you're more likely to keep up to date.

Now the digital world is pushing us you know, to remain at the frontier to keep progressing to keep advancing. So we should see the digital world is not an empowering word as a world that actually transforms you know better skill to the backdrops and better lives. And that seems almost direct relationship between between the skills in population here I measure literacy and numeracy skills through our server fuddled skills, and the risk of automation.

On the left side, you see countries where labour markets are not so much at risk to be automated. By you can see also these are countries where numeracy skills typically cannot be well developed, you go towards the right side. These are countries where numeracy skills seem to be less developed in the workforce, and the risk of automation seems higher. So seem to be great insurance against the risk of automation for individuals and for nations.

Now, this is what people in the workplace does. When you look towards the young people now in our latest PISA survey, they asked teenagers, young people at age 15 What are their dreams for the future? What are their own aspirations? And it's quite frightening that you have many countries where you have you know, 40%, sometimes over 50% of young people looking for jobs that may no longer exist when they graduate.

A very large chunk of teenagers, and even more so among disadvantaged groups aspire to jobs that have disappeared. They don't seem good enough to give Yeah, People better signals about the evolution of labour demand about the nature of jobs in the future. And that is so important.

You know, if you have never seen a scientist was a scientist, why would you start to study hard in mathematics and science subjects that are difficult? One of the six, we've also seen that the Korea concentration, basically the educational expectations, has not, you know, declined, but increased.

Think about it. The diversity of jobs in our labour markets is rising, you know, we get more and more kind of complex jobs, modern differentiated kind of workplaces and so on. But actually, the occupational expectations of 15 year olds have narrowed, become more by myopic between the year 2000. In the year 2018, particularly so among girls now, think about it in 2018, half of the 15 year old girls look just for 10 jobs, among hundreds of jobs.

How can we change this? Now that brings me to the toughest part one i people prepared for the digital world. When we looked among older people, you know, 55 to 65 year olds, you can see in, on average, across countries, we're talking about one in 10, older workers, who were better protect, for those who are better prepared for the digital world.

They have, you know, problem solving skills with which they can manage complex digital information. country like the United States, New Zealand, we're better positioned on this, but overall, you know, actually, a lot of older people lack the skills they need for today's digital economy.

Now, I know you're gonna tell me, Well, that's all soft. And among, you know, the digital natives, the next generation has accumulated all of those skills that are required. And actually, yes, the bars get longer when you look at the skills of 25 to 34 year olds that we also tested in our server for Dell skills.

But if you look at it's close enough, not only talking about every second 25 to 34 year old, reasonably equipped for the world in which we live today. being integrated digital native doesn't imply that you have the digital skills that are needed to be successful in our world, in our economy.

And also the rank order of countries, it's changed quite dramatically. Look, you know, the United States used to be at the frontier among young people is just in the middle of the pack, not because things got worse, but because things got so much better, so much quicker, and other countries.

Very same picture for the UK, UK used to be at the frontier. That's why you know, workforce qualifications today are quite good. If you look at the incoming cohort, you know, moving into the labour market, things such as so so you see the opposite picture in a country like Singapore, you know, they used to be the laggards and the older generation or education was very limited.

Today, they're at the frontier together with countries like Finland, and Sweden. So the global talent pool is going to look very, very different geographically ended up across different groups.

The drivers behind those developments are not difficult to understand the kinds of things that are easy to teach easy to test routine tasks, you know, have also become easy to digitise to automate, to outsource disappearing from our labour market, technology intensive tasks are on the rise, you put the two things together, you get a pretty clear picture of the future of work. Some people call this a race between technology and education.

You know, before the first industrial revolution, neither technology in our education merit for the vast majority of people, people lived happily and self sufficient.

On the front end came the first industrial revolution, moving technology ahead of the skills of people and causing huge amount of social pain.

People that badly prepared for the new technologies. But then, you know, that's when we started to build, you know, education system, the kind of systems that we know today, making people compatible with the ideas of the industrial age and its credit generations of prosperity.

But if you're honest, you know, we haven't actually changed the model very much since those days and today, you know, we are seeing the digital revolution now once again, moving technology ahead of the skills of people and causing the same kind of social pain with young people leaving university was great degrees and having difficulty finding good work and at the very same time, employers say we cannot find people with the skills we need.

That's a dilemma we need to solve no more We once again know people ahead of the technologies of our times. You know, to put this in quantitative Trump's, when we tested, you know, literacy skills of adults, we found around 20%, you know, perform very poorly not 20% of adults in the OECD countries in the wealthiest countries, you know, have literacy skills that you would expect from a 10 year old child.

And you can say, well, for many, it looks better. For some it looks good. And for a few, it looks great. And then we ask ourselves a question.

And what if we asked, you know, modern computer, artificial intelligence to solve those very same problems that we gave to humans in this literacy test?

And actually, the answer is, the near term computer capabilities come close to the 70th percentile of humans. This tells us actually, many of the skills that we are developed developing today are quite commonplace. We need actually to become much better to develop a different skill profile.

Success is no longer just about literacy and numeracy. We need to think hard of providing people with a reliable compass and the tools to navigate with confidence through a world that is increasingly complex, volatile, and biggest capacity of people to imagine, to create, to resolve and manage tensions and dilemmas not to live with themselves to live with other people to live with the planet.

It's about cognitive, social, emotional resources that we need to develop, if we want to make people you know, you know, fit for the for the workforce of tomorrow. And for life of tomorrow.

Our education systems know how to educate second class robots, you know, people are very good at repeating what we tell them. We need to think harder about what makes us human, in the time of artificial intelligence, how we complement not substitute the artificial intelligence be created in our computers.

You know, today, our eyes are very much fixed on the pandemic. But actually, the future will always surprise us, you know, clearly, climate change is going to transform our lives more radically, then this pandemic, artificial intelligence is probably more disruptive than the pandemic, in many ways he cannot even imagine and then there'll be many other forces are transforming the context in which we learn a war.

We cannot predict the future. But we need to become better to think about alternative futures, to imagine to project to build scenarios for the future. If we are more agile if we are better capable to navigate out to alternative futures, but probably be better prepared for the future that will eventually materialise.

Let me know highlight a few of those scenarios. Of course, one of the scenarios is simply the status quo.

Now, our education systems will just you know, little bit improve gradual development. And you might dismiss this particularly now, after the pandemic, people say no, everything is going to be fundamentally different.

One, actually, you have said that many times in history, and actually our education systems have proved to be remarkably resilient to change the gap between what our societies expect and what education delivers, hasn't become narrower, it's become wider, not everywhere, there have been some countries with enormous change.

And if I look, for example, here is the average skill level in the older generation, you saw that before. And here's the skill level in the younger generation, you can see overall, you know, things have progressed on our survey of adult skills when we gave people a test. And in some countries, much more so than what you can see here, for example, Singapore started out, you know, very poorly now, and the young generation is doing quite well.

Children not moving from poor to better off, still very much behind but actually can see the progress. France, you know, moving from below average and the older generation, to average, you can see Germany, you know, studying where the older generation was about average, you know, generation is a little bit better than average, Lithuania, you know, New Zealand, but then you get to the United States. In the United Kingdom. The older generation performs reasonably well. The young generation doesn't do any better. Imagine this.

Young people in the UK moving into the labour market are no longer better skilled than those getting up for retirement and it completely changed labour market. So there is no inherent automaticity that our education systems we'll adapt to changing requirements.

That is something that requires a lot of policy initiatives. Education is a remarkably conservative social enterprise. And you know, sometimes we as parents are part of the problem, not part of the solution, we get very anxious when our children no longer learn what was very important for us, and they get even more anxious.

When they do learn things we no longer understand. Teachers are often more likely to teach how they were taught and how they were taught to teach him as a policymaker, you can lose an election of education when something small gets wrong, but you rarely win an election over education, because it's simply very, very hard, you know, takes a long time to translate, you know, good ideas into better outcomes.

Well, you know, another scenario, simply, you know, one day, education systems will crack apart under the pressures of, you know, acceleration, like everything else in the digital world, as people will start to, you know, walk with their feet, look for alternative education resources in their amazing opportunities for this.

Artificial Intelligence offers us entirely new learning experiences, making learning more interactive, more granular, more adaptive to the individual needs of individuals.

When you study mathematics on a computer, the computer can study how you study, and then you know, tailor learning environments, to your specific learning needs.

Evaluation and Assessment. You know, one of the biggest mistakes we've made in learning is to divorce learning, and assessment. You know, we pile up lots of knowledge. And then, you know, one day we asked students come back and tell us everything you learn in a very constrained, artificial, narrow environment.

And if you future, we can integrate learning and assessment, giving students instant feedback to help them learn better, giving teachers instant feedback for how their students are progressing. And helping policymakers understand something more about the effectiveness of education.

Learning Analytics gives educators so much better tools to see how different people learn differently and to embrace that learner diversity with more differentiated pedagogical practice.

But, you know, the reality is actually, when we looked at this, in our latest PISA study, that actually technology intensity tended to be negatively related to learning outcomes. Better technology doesn't automatically mean better learning outcomes. Sometimes it can make learning more superficial, technology is only as good as its use, we have to become much better to design pedagogies, around 21st century technologies.

In other scenarios, yet, schools become you know, more hubs of learning, integrating into a wider range of social functions. Now, you can see that in the Nordic countries, maybe in Canada, let me know, make one more scenario here.

And that is, you know, one day maybe every single unravel, and we will learn anywhere, anytime, any people will just be on their own, there will be so many devices around us that help us, you know, push us learning, you know, learning through our lives, in ways that we cannot imagine today.

But, you know, it can said likely today, this very, very live little investment in innovative capacity of our education systems. Global venture capital in the field of education is so tiny compared with adults, and it's so much concentrated, you know, 2014, it was mainly about a story about the United States nowadays, is mainly a story about China, Europe, you know, you can see this tiny kind of slipped in this trap, we're not actually making the investments to keep education innovating in a way that you would come to transform itself.

Last but not least, you know, we used to love to do the work now. And now learning has become the work. In the past everything used to be quite simply, you know, credit score, you go to a university or vocational education, you work and then you retire.

Well, in the future, we need to invest a lot more in earliest Yes. Now, we know that some of the social and emotional capabilities that are so transformational for people, I develop in earliest use brain sensitivity is highest.

And, you know, learning in the university sector needs to be a lot more open a lot more transversal. And then, you know, learning a working need to be integrated.

The future places of work will be future places of lightning. But that raises some really difficult questions for us. How is the additional funding shared between governments employed, and beneficiaries?

What are the incentives for people continue to learn? Who will set the standards? Who will accredit that learning? How will we recognise levels of skills?

Firms are learning environments, we need very, very different kinds of tools. How do we certify skills in a digital world? You know, everybody talks about microcredentials. But how do we build a more coherent currency that, you know, gets people moving and gets people you know, recognising investment in skirts and gets employers understand what employers can actually do? How do we diverse people, outside firms?

While the unemployed it's pretty clear, you know, government funding will probably pick the bill up for that. But you know, what about the people who are at risk of losing that job? Who's going to invest in today's truck drivers, then we know that their jobs are unlikely to exist and 20 years down the road?

Whatever we do, are people who want to change that jobs. What do we do about the gig economy where people are not so well organised in labour markets?

So that's a question we should be answering today. And new forms of work of means, you know, fewer forms of taxes, governments will lose a lot of you know, direct control when labour markets become more abstract mind form. These are the questions we need to be answering for tomorrow.

So all about you know, assessing risks and leveraging opportunities. What is the right balance between modernising and disrupting our skill systems? And how do we reconcile new goals, this old structures? How do we match the global was the local?

How do we, you know, advance and innovate our education systems in a very conservative social environment? How do we realise potential with existing realities, the existing infrastructures?

And how do we balance education and learning? How do we, you know, reconfigure this space as the people that time have the technology to educate learners for their future, rather than our past? Without you're going to find good answers for these questions at this conference? Thank you very much.

The pandemic has widened the skills gaps because a mix of digital transformation, high demand for certain skill sets and a lack of quality training providers mean organisations are struggling to find the right talent at the right time.

Solving the skills gaps requires educators, training providers, businesses and government to come together to equip employees with the right skills – and mindset – to thrive in the future of work.

Any organisation looking to future-proof their talent strategies needs to understand the skills they already have and the skills they need to develop in the future. As with all organisational structure work, this needs to start with your company goals.

Consider:

From here, you can begin to identify the roles needed to reach these targets.

Next, think about the skills needed for each of these roles. Take an inventory of your current workforce. Which skills do you already possess? Which can you upskill your people in? And where do you have a skills gap that needs to be filled?

Once identified, you can begin to close your skills gaps through external hiring or by commissioning training providers to upskill your people.

This panel of education industry experts, chaired by Carl Ward, Chief Executive of City Learning Trust, considers the skills required for the changing world of work and why greater emphasis must be placed on core transferable skills like creativity, problem-solving and innovation.

Note: click through to find a summary and transcript of this video.

The Great Resignation and the ongoing war for talent has made recruitment more expensive, more time-consuming and more difficult.

At the same time, half of the world’s workforce will need reskilling by 2025 to meet the challenges of technology and automation, according to the World Economic Forum.

These twin issues mean organisations are having to rethink what effective skills development and future planning look like.

The solution?

Learning and development has never been more important to the success of business, to the retention of employees and to the future of work.

However, traditional learning methods are often outdated and ineffective, with employees faced with one-size-fits-all classroom programmes or ill-fitting training providers that are neither applicable to their working lives nor able to provide them with skills to develop in the future. This leads to poor take-up of learning programmes and low employee engagement.

This need not be the case. According to PwC’s 2021 Global Workforce Hopes and Fears Survey, 80% of employees are confident they can adapt to new technologies entering the workplace, and 77% are willing to learn new skills to remain employable.

Pete Brown, PwC UK’s Joint Global Leader, People and Organisation

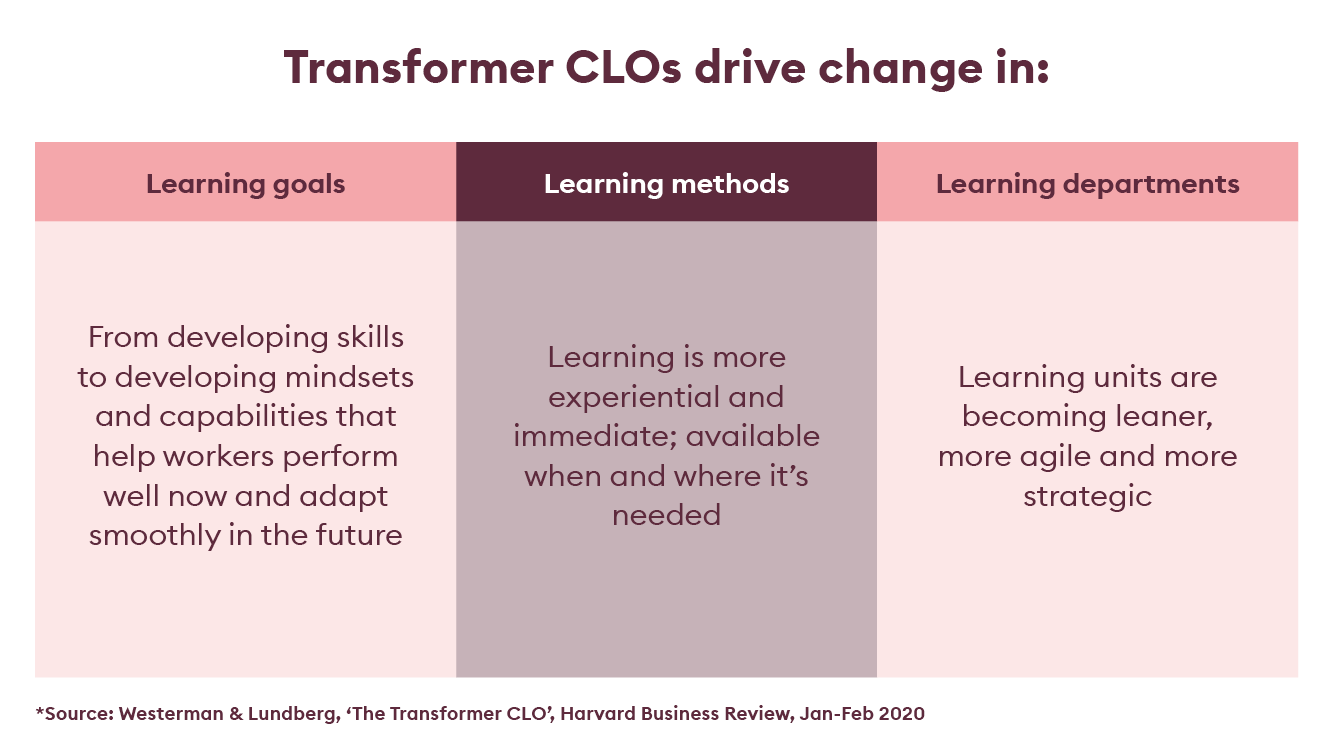

To keep pace with rapid change, leaders and businesses are required to take a transformative approach to what learning and development looks like. Harvard Business Review’s 2020 article The Transformer CLO expounded the idea that the role of a modern chief learning officer wasn’t just about being a training provider, but about creating an holistic learning culture.

This means ditching the ‘chalk and talk’ style of learning and looking to training providers that offer personalised, digital, atomised training.

This modern take on learning acknowledges how individuals learn best, tailoring programmes to how each person takes on information. It introduces elements of artificial intelligence and gamification to put employees in real-life situations so that they can practise the skills they’re taking on board.

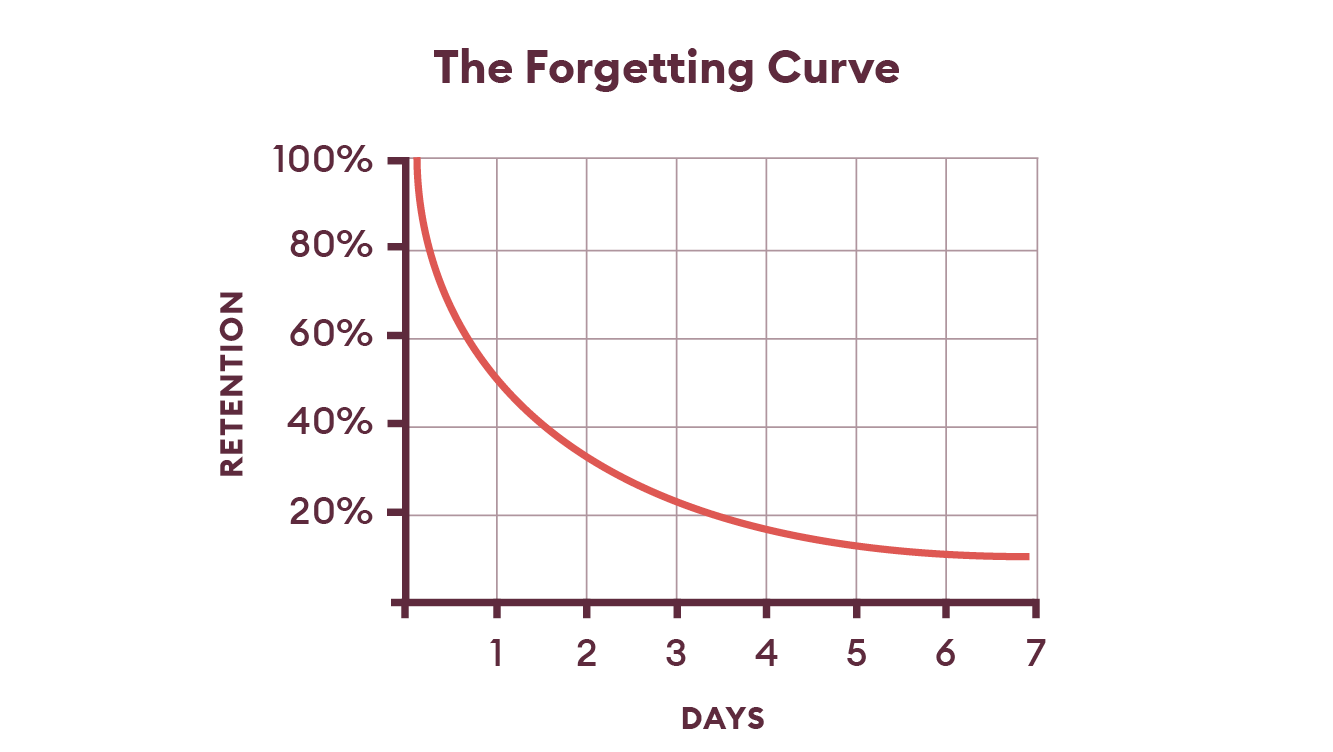

As far back as the 19th century, German psychologist Hermann Ebbinghaus experimented with how people memorise information. He posited the Forgetting Curve, which suggests that the longer we leave it to apply new information in practice the more likely we are to forget it. Leave new information for an hour, and you’ll remember only 44% of it. Leave it a day, and it goes down to 34%. By two days, you’ll only remember 21% of new information. Practice truly makes perfect.

Of course, the main reason the future of learning is the future of work is because of the pace our world moves at.

To thrive, we need to continually update our skill to enable us to take on new challenges. As Future Talent Learning’s CEO Jim Carrick-Birtwell puts it: “In the age of technological change, staying ahead depends on continual self-education – a lifelong mastery of new models, skills and ideas. Becoming a learner is one of the most important skills you need to succeed in the 21st century.”

The reason learning has become so important to organisations is that many are struggling with a huge skills gap in their business.

According to a report by McKinsey & Company, 87% of organisations say they are currently experiencing a skills gap, or will do so in the next couple of years.

This is exacerbated by the pace of technological change. A Gartner study found that 64% of managers think employees are unable to keep up with the need for future of work skills, with 70% of employees saying they haven’t even mastered the skills needed by their job today, never mind in the future.

Rather than relying on governments or training providers alone to fill this gap, companies are increasingly seeing it as their role to build and develop required skills in their people. Take banking giant JPMorgan Chase as an example. In 2019, it announced a $350 million investment in a new skills development programme aimed at future-proofing the organisation’s skill set focusing on technological advances and future business trends.

Jamie Dimon, JPMorgan CEO

The economic case for upskilling is stark. According to the Upskilling for Shared Prosperity report by PwC and the World Economic Forum, upskilling has the potential to transform whole economies.

It posits a scenario where countries upskill workforces in line with OECD industry best practice by 2030. This would lead to a global gain of $5 trillion. Accelerate this process and achieve upskilling by 2028 and the economy could grow by $6.5 trillion, with productivity up 10 percentage points.

With the global economy in turmoil, together with a climate of uncertainty, upskilling and reskilling have become much more prominent as key features of organisations’ talent strategies. But taking a skills-based approach requires companies to think very differently about their recruitment and development practices.

Against a backdrop of talent shortages and high employee turnover, creating a learning culture where employees are encouraged to develop, grow and drive business forward is key to getting ahead. After all, growing your own talent is the best way to combat talent scarcity.

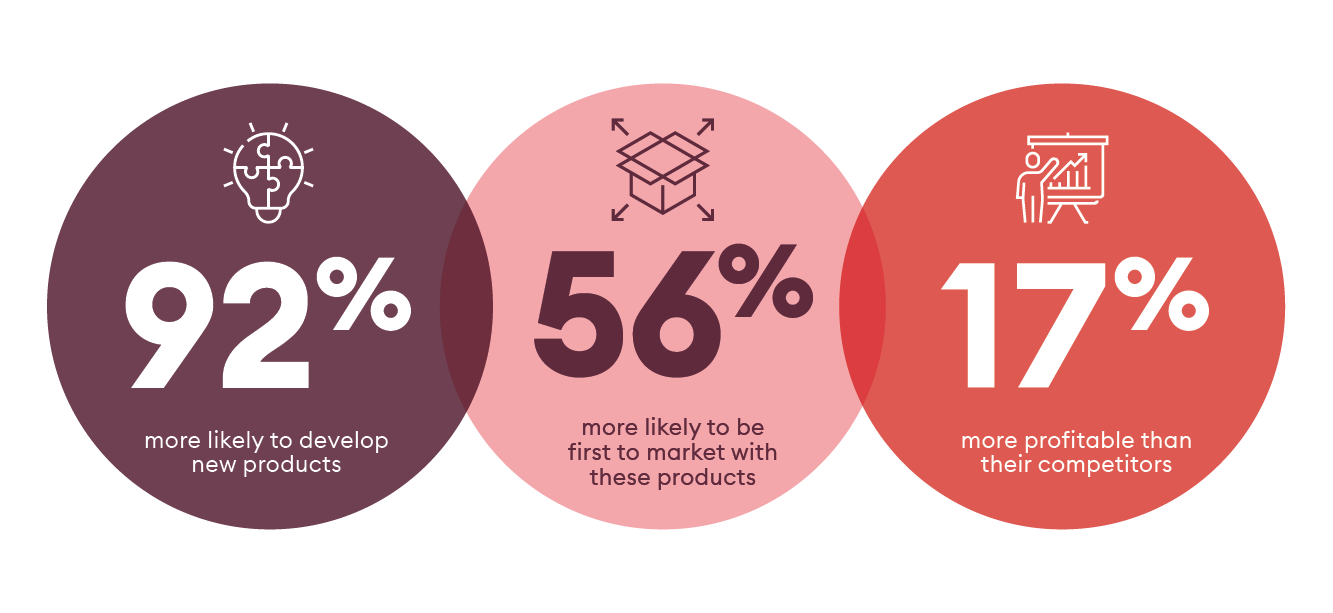

A strong learning culture also increases a company’s agility, creativity and ability to grow. Consider a Deloitte study which suggests that organisations that embrace learning are 92% more likely to develop new products, 56% more likely to be first to market with these products and, ultimately, 17% more profitable than their competitors.

When it comes to hiring, upskilling your people to meet future of work challenges provides economic benefits alongside cultural ones – at least according to HR thought leader Josh Bersin.

“The cost of recruiting a mid-career software engineer (who earns $150,000-200,000 annually) can be $30,000 or more including recruitment fees, advertising, and recruiting technology. This new hire also requires onboarding and has a potential turnover two to three times higher than an internal recruit. By contrast, the cost to train and reskill an internal employee may be $20,000 or less, saving as much as $116,000 per person over three years,” writes Bersin.

Too many organisations are stuck with a traditional solutions-based approach to learning. Here, employees are taken out of the working environment, placed in a classroom and taught theory on whiteboards or through boring presentations.

This is not how people learn best. Modern learning and development is about personalised, interactive, situation-based learning that learners practise in real-life scenarios. It’s about social learning, where people share ideas and experiment with new ways of working outside of a traditional learning environment. In short, it’s about creating a learning culture, rather than learning interventions.

The idea here is that learning is no longer something you do – which takes you away from being ‘productive’ – but something that happens naturally as part of the working day. Achieving this means working with training providers who understand how to create programmes that allow employees to apply learning to real life. It’s about encouraging a learning mindset that is curious, creative and agile, and understanding that capabilities fuel productivity.

Do this and you’ll find productivity increases, not decreases.

We know that digital technology and automation are transforming the world of work, forcing employees to continually update their skills to stay relevant.

At the same time, we also know that business leaders are facing a huge reset in the skills they need to keep their organisations functioning in the future of work.

What we’re less clear about is what those skills will be – and how we develop them in our people. So, with manual and physical skills on the decline, what exactly are the ‘human’ skills we’ll need to develop?

Disclaimer: If you are able, we strongly encourage you to watch this video or listen to its audio. Transcripts are generated using speech recognition software that has been checked by human transcribers but may contain errors. Please check the corresponding audio before quoting in print.

Summary keywords: talk, people, friends, work, scientists, lab, cloud, resilience, conversations, thought, breakthrough, loneliness, compete, alastair campbell, blindingly, british establishment, competitive environment, motivated, incredibly high standard, creative

Margaret Heffernan 00:10

I'm going to talk about Uri Alon. Uri's a scientist and I spend quite a lot of time with scientists, not just because I'm married with one, to one, but because I'm really interested in how scientists do what they do. Because what they do is they find really hard problems. And they try to solve them generally in a very competitive environment, generally not enough time, and very, very little glory. And I have this kind of hypothesis that if I can figure out how they do that, then we can all figure out how we do that. Because if you're coming into areas like innovation, what innovators do, they find really hard problems and solve them in a competitive environment with very little time, but sometimes lots of boring so it's a really interesting guy.

He's made enormous breakthroughs in the area between biology and physics. He works at the Weitzman lab in Israel. And he's famous for many of these scientific discoveries, but he's most famous of all for a scientific paper that he wrote, called how to run a motivated research team. And you might expect that like other scientific journals, this article will be full of diagrams and equations that you can't really understand. But actually, it's full of all sorts of things that are just kind of blindingly obvious, except that we mostly go through life, not see. And when I asked story why was it his lab was so incredibly productive.

They told me a really interesting story. And it segues very beautifully with what Alister and Jack were talking about. When he was a postdoc, and he was darling, really the beginning of his current work. There were times to get out of bed in the morning because he felt so tired and so confused and so anxious. He felt he was really hitting the buffers of his own capability. And he thought, maybe I'm not meant to be a scientist. after all. Maybe I don't know what I'm doing. Maybe the project is wrong. Now he was just completely lost and confused. And he described it as being in a cloud because he couldn't tell which way to go.

And I said to him, So what got you through that? And he said, I had some really great friends. I had just a few really great friends. And they came up and they'd support me or they take me out for a drink or they'd give me an idea, like scream at me or they'd laugh with me and they somehow seem to know what I needed. And then when I got through, and I looked back and I thought, How did I do that?

They would just kind of their way. And say, well, we need like we need friends. We need friends. Now. It's hard having friends at work and it's probably hard having friends at work because we're not really brought up to think that work is a place where we're going to find or make friends. Work is the place where we're going to compete, where we have to out compete out, work out, prove ourselves to those around us. And of course if we maintain that attitude, highly inculcated school, it makes work particularly difficult. Because really work.

The excellent isn't really enough. What you need to do is to be trusting is to be trustworthy. And if you're going to be trusted and trustworthy, it's going to be because you trust other people, and you're generous, and you help them and instead of competing with them, you support and encourage this secret of ory alongs lab, as it turns out, is that he insists that every in every week lab meeting in scientists mostly have lab meetings on Tuesdays two hours first thing in the morning.

Why I don't know why. But the first half hour of Murray's lab meeting is unusual because he won't let any of his scientists talk about science. Now, scientists don't want to talk about anything else. But he insists you can talk about politics or theatre or or sport or your kids or the weather or whatever you want to do, but you may not talk about science. And the reason that Laurie did this, he told me was if he realised that mostly what is scientists in his lab would come in and do is it come in, and they'd start working really hard, and they compete with each other wildly, and then they'd go home at the end of the day. And he said, as long as that's what they did, nothing got done. And so he introduced this half hour just as an experiment.

Scientists always because he said I want people in my lab to see each other not just as scientists but as human beings. And I want them to see that they have a lot in common with people who don't look like them or sound like them or come from Israel. People who aren't Jewish or people who aren't male or people who aren't female, people wildly different from them, can still care about them. And what it means is that when they hit that cloud, and they will hit it if they're doing anything worthwhile. They know they are surrounded by people who will get them for it. And this is meaningful to me, not just because I care hugely about that kind of moral spiritual, emotional atmosphere.

But because in any kind of company if you're going to do breakthrough, creative, interesting work, you too are going to hit that cloud. And you can either back out and never do anything interesting. Or keep going because other people help you. And this is never more the case than when you encounter something at work. That makes you uncomfortable. And nervous. You makes you wonder is that right? I hear that right. Can that be true? Did he really say that to her? Did she really not get heard at that isn't really the case that nobody's ever mentioned such and such. Talk to an executive the other day said, you know, it's incredible.

I work in the hotel industry and for five years we managed never, ever at any board meeting to talk about Airbnb. How did that happen? I'd like to know how many conversations weren't had at Facebook. I know that when Facebook came out there were conversations that didn't happen in Google. And what gives people the courage to say hey, this is kind of interesting. We should think about this. You know, I really don't think that is quite what we aspire to. Or are we really sure we want to cut those jobs because Don't you think you could leave our customers or patients expose to have those conversations, the breakthrough conversations? Alastair Campbell's quite right it's not about courage. It's about support. It's about sounding boards.

It's about having people you can try these conversations out with and who will tell you the truth. They'll tell you actually more about your ideas nuts, nobody's gonna listen because we tried it five years ago and tomorrow, or they'll tell you I think that's a good idea, but you should go to the meeting with similar people or probably don't use the rude words you know, they're probably not going to advance your case very much. We need people around us who are sucking up to us who aren't afraid of us who aren't competing with us, but who want the best for us. Who can put their agenda aside every now and then when we need to help us understand what ours is and how we can advance.

Now, I organised a session about a year ago for about 70 executives, specifically to talk about this subject of friendship. And I brought into very eminent chief executives. Who talk very candidly about the professional and personal crises in their lives, and how they could not have got through those races without each other. These are big, serious, important men at the top of the British establishment, saying actually, I couldn't have done this without a friend who had my best interests at heart. And afterwards, I went on a walk with a number of people who've been in the audience. And they all were quite moved by what they heard. But they said, you know, you don't have any time to think for friends.

I mean, I remember I used to have friends. But now I have, you know, kids, husband, family and I just work and there's just nothing left. There's just nothing. And as we walk this great cloud of loneliness descended on. And I thought this is the moment in this cloud justice arena Longstaff when you don't know which way it is, this is the moment at which the risk of making the wrong turn is the most acute.

When you might back down or you might fly off the handle, or you might give up. And that's the moment if you're going to do anything interesting. If you're going to do anything meaningful and valuable in the world. That's the moment that you're going to need friends.

Now, this is personal for me. It's not just theoretical. It's not just because every chief executive I have ever known sooner or later has talked to me about the friends that got them to where they are and it's not just about having friends who can climb up the ladder. I am not talking about networking. I am talking about soulmates people different from you who can see your qualities. I'm talking about people who care and don't think that's a sign of weakness.

I'm talking about people who may be competitive, but not with you only for excellence. And of course I'm talking about myself. One of the things I'm most proud of is how many of my former employees I'm still friends and I probably even prouder of how many of them are still friends with each other to the point that they now will recruit each other because they want to keep working together. Because yes, their colleagues and yes their co workers, but they're friends and it's why they can do such tremendous work together because they have all of that generosity and trust.

That when you roll it all up we call social capital. The social capital that makes the organisations they work with, truly resilient, strong enough, confident enough, eager enough, ambitious enough creative enough to get through the cloud. To create something the world has never seen before.

And it's personal too, because when I was 30 years old, and just two years married. My husband was killed and I was in a big powerful job. And what got me through that, and through the court case and through years of misery and loneliness. What got me through that? Were my friends. Yeah, my family is helpful too. Of course they were you kind of expect that. But the friends were the people I used to wear at work every day.

The friends were the people at work, who realised if I was having an off day, that they'd cut me a little bit of slack. The friends were the people who realised that I didn't have anyone to go home to anyone. And yeah, it would be nice to go out for a drink or two movies or something to pretend I was still human until maybe one day I would be again. And it's personal too because one of my best friends died two years ago.

I've met him through work. He was a brilliant, inspiring funny, ly. Intelligent, wicked, harsh critic and I feel he's still with me. Because every time I try to do something difficult and stumble, I see him standing there thinking, Oh, go on, pick yourself up, keep going. Don't quit. Why would you? That's not what we do.

And every time I do something that I think always said, Okay, I sort of see him on the sidelines saying, yeah, it was okay. You could probably do better. And every now and then I just see him smile and I think Wow, that must have been really but I couldn't do any of the things that I've done. If I didn't have those people inside me and outside not because of their contacts, not because of their know how not because of their power networks. But because they feed my sense of myself, and they hold me to an incredibly high standard.

And they remind me that anytime you're going to do something really outstanding, meaningful, valuable something in the world. That matters. You cannot do it. You look at any grapefruit, of any kind, any real achievement and you can trace a family tree of friendship.

Now we've talked a lot about resilience. We talked a lot about the kind of networks you need for political resilience. We've talked a lot about the kinds of attitudes to physical health and mental health that requires resilience and we've talked a lot about resilient where resilience comes from. Let's don't forget that resilience is about the power to keep going. When things get really difficult. The ability to absorb pain and doubt and confusion, and I find the ability to see that there are reasons to keep paying for my money.

What gives us those reasons is each other for all the creative people I've worked with all the creative organisations say what keeps people motivated and ambitious, the best in themselves and the best in each other is just each other.

17:10

Thank you very much.

There are many definitions of the skills we’ll need in the future of work, but almost all reference the need for emotional, social and interpersonal skills – ‘human’ skills that help people build relationships.

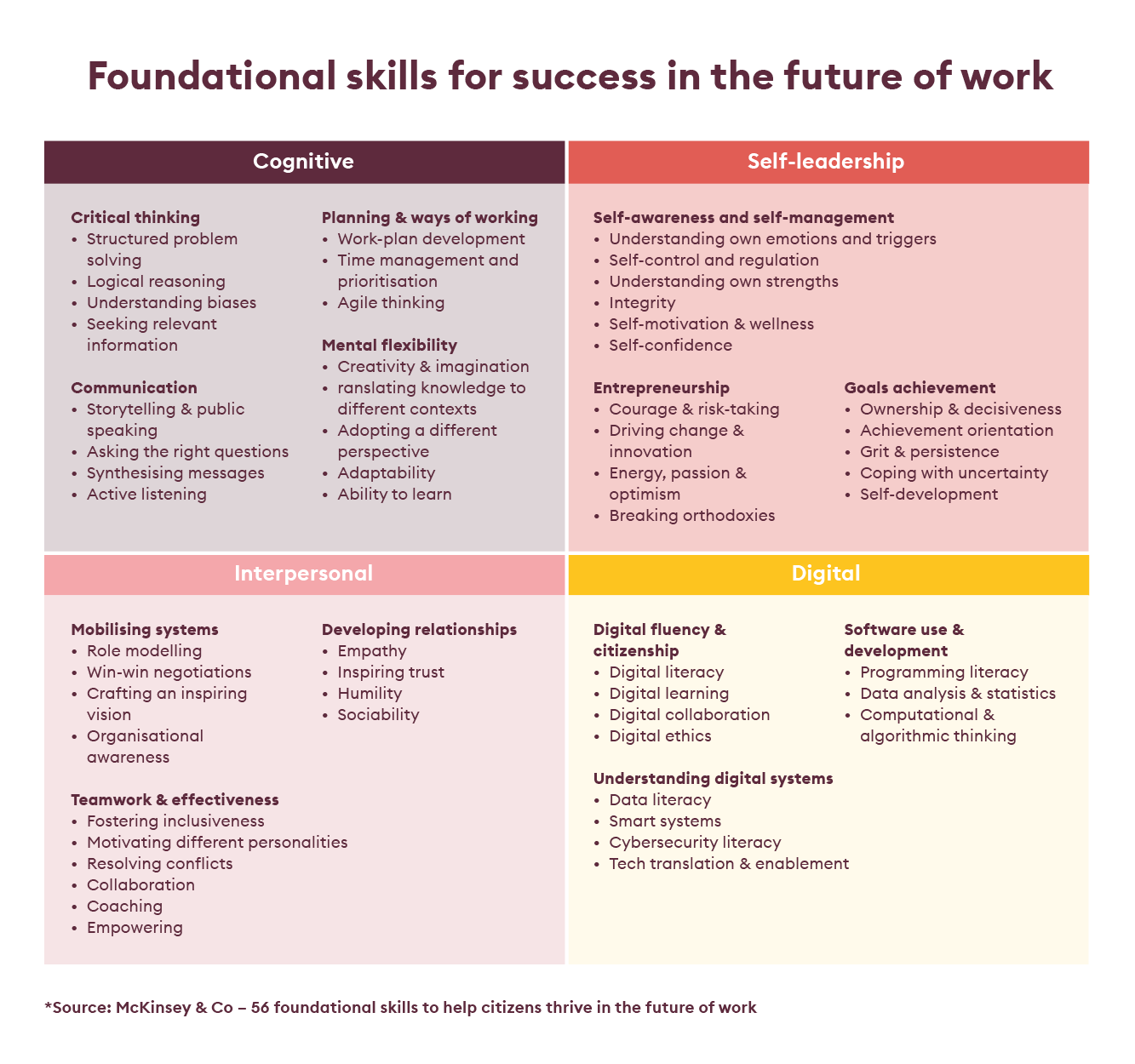

Research by the McKinsey Global Institute examined the skills employees will need to thrive in the future of work. The report identified 56 foundational skills it believes will define the future of work – with many already linked to higher income, job satisfaction and employability.

Each skill had to fulfil one of three criteria: add value beyond what can be done by automated machines; allow the individual to operate in a digital environment; and allow the person to continually adapt to new ways of working.

These future skills are then split into four categories: cognitive skills such as critical thinking, communication and creativity; interpersonal skills including collaboration, inspiring trust and conflict resolution; digital skills such as data analysis and digital learning; and self-leadership qualities including resilience, risk-taking and self-motivation.

What is striking from the research is how many of these future of work skills are human qualities. Rather than technical know-how, the future of work is about how we interact with, influence and engage our fellow people. Human skills around developing relationships, mental flexibility, teamwork and emotional intelligence are the abilities that will define future success.

Let’s list some of the most important human skills needed for the future of work.

What is striking about these future of work traits is that so many of them are behaviours – not just skills. With technology set to automate much of our day-to-day tasks, the future will be about how we build relationships, adapt to change and manage complexity.

So, how can leaders build these skills in their workforce? As with most cultural shifts, it’s important for leaders to exemplify the change they want to see. This might be about senior leaders seeking out training providers that offer human-centred skills training so that they can develop their own emotional intelligence and leadership style.

Then, it might be about developing a learning culture in the organisation, where all employees are empowered to personalise their learning and develop at their own pace. A transformational learning and development department will move away from developing specific skills to developing mindsets and capabilities that allow employees to continually grow and adapt to change.

Ultimately, it’s about seeking out training providers that can help you change at an organisational level, not just an individual level.

There are many training providers offering programmes that teach these new skills in leadership and management. However, it’s important to consider how learning has moved away from a classroom-based model to a more personalised experience.

Future learning is about collaboration and co-creation rather than being based on a teacher/pupil model. How can you help your people take control of their own learning and partner with colleagues to solve problems?

Secondly, the training providers you use should embrace digital technology and offer opportunities for virtual learning. Learning can happen anywhere and at any time. Technology means information is just a click away, while social learning platforms allow learners to come together and learn in a more informal way.

Digital technology is empowering learners. With this comes the need for individualised learning plans. We know that not everybody learns in the same way or at the same pace, so it’s important that the training providers you use can personalise learning offerings to make sure everyone has the opportunity to learn in the way that suits them best, via a variety of methods and experiences.

Above all, learning needs to be applied. Can your training providers place learners in real-time, real-life situations where they can test out their learning? If so, how do they document the experience and guide learners through the process?

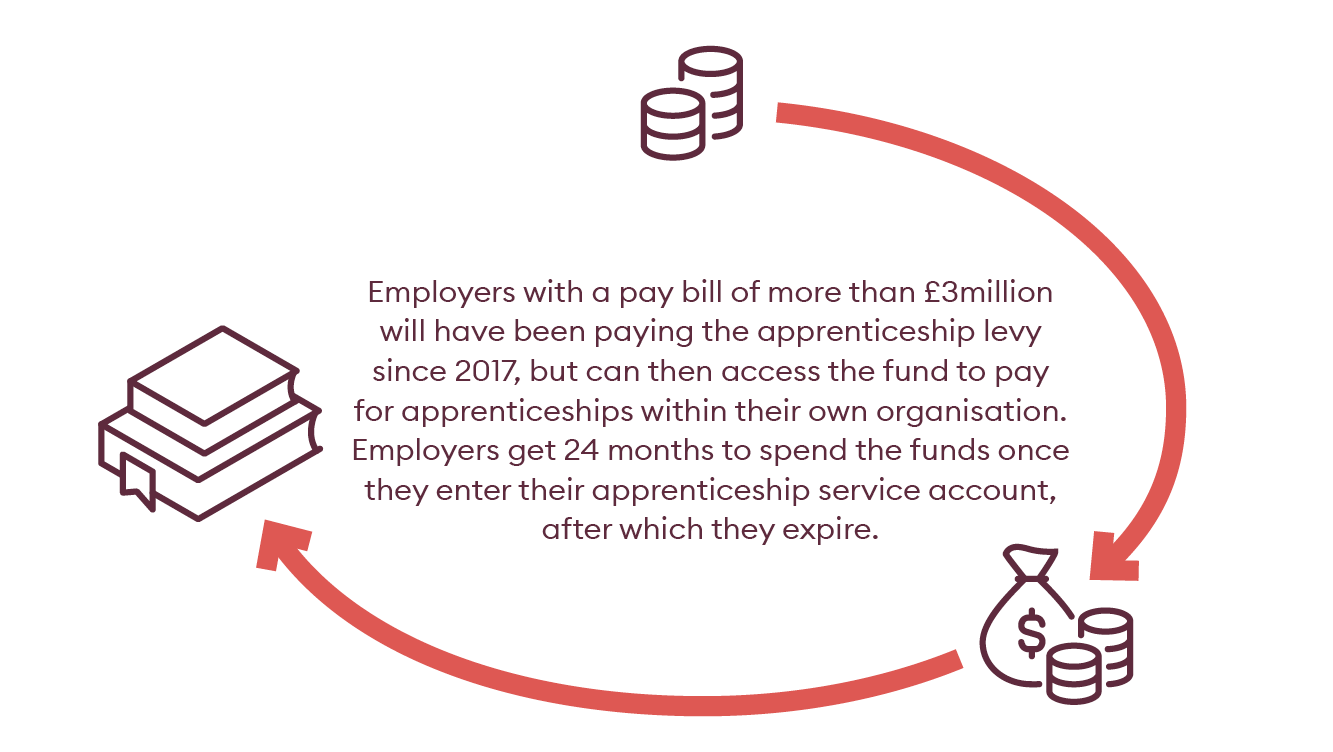

One way of funding training for future of work skills is through the Apprenticeship Levy. Created by the UK government in 2017, the Apprenticeship Levy is designed to help business owners in England invest in apprenticeships and training programmes to develop new skills in their workforce.

Employers with a pay bill of more than £3 million will have been paying the Apprenticeship Levy since 2017 and able to access the fund to pay for apprenticeships within their own organisation. Employers get 24 months to spend the funds once they enter their apprenticeship service account, after which they expire.

Using the Apprenticeship Levy allows employers to access fully funded training programmes that can develop human-centred skills in their organisation.

With a commitment to investing in development and growing a new culture of learning, Anglo American was looking to partner with a leadership development provider experienced in virtual delivery.

The company’s Leadership Academy consists of a number of programmes for high-potential leaders at various levels. One of these is the Achievers Programme for first line leadership talent.

Achievers was evolving from face-to-face delivery to a fully virtual design, giving the programme wider reach and opening it to an audience currently prohibited by travel time and cost. The Leadership Development team had aspirations for this new programme to be fully virtual, globally accessible and customised to reflect the organisation’s purpose, burning ambition and values.

Roger Minton, Head of Leadership Development, Anglo American

Anglo American worked with Future Talent Learning to deliver the Transformational Leadership Programme and also customise its Achievers Programme. Learners are engaged through innovative content delivered through experiences and challenges, virtual simulations and gamification. These activities are all designed to equip participants with the leadership skills, behaviours and mindsets to succeed as future leaders with the confidence to apply new learning immediately in the workplace.

Tripartite coaching sessions bring learner, line manager and coach together for proactive discussions, providing an opportunity for the line manager to hear progress, give feedback and connect conversations to wider development plans.

Roger Minton, Head of Leadership Development, Anglo American

Future Talent Learning’s Transformational Leadership Programme has enabled Anglo American to accelerate 100% virtual delivery of its Achievers Programme focused on developing first line leadership skills.

Through working with Future Talent Learning on a fully customised talent programme, Anglo American is creating a culture of learning while equipping its future leaders with the skills and approach needed to thrive.

Roger Minton, Head of Leadership Development, Anglo American

Want to read the full article at your leisure or share it with a colleague?

Enter your details and download.

Change Board Holdings Limited,

trading as Future Talent Learning,

Main Apprenticeship Training Provider

UKPRN 10084912